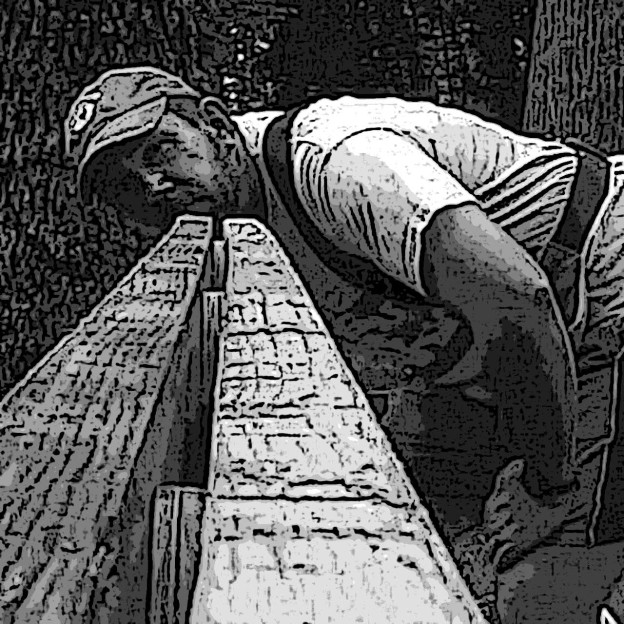

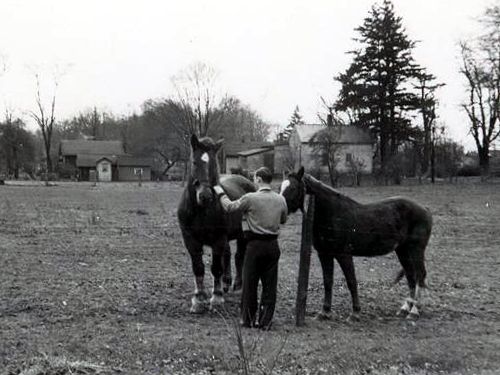

Passing along skills from generation to generation is a strong theme in An Irish Miracle. As a ten-year-old boy on an Ohio family farm in 1955, Alex is excited to learn how to weld from his father, Jake, so he can fix a broken plow. An older Alastar passes along the skills of caring for horses to the younger men at Glencoe Stables.

The tradition of passing along manual skills takes many routes, a few of which are:

- Father to daughter or son

- Mother to son or daughter

- Journeyman to apprentice

- Mentor to fatherless child

- Shop class

Sadly, many high schools across America have discontinued shop classes, as more and more students prepare to become “knowledge workers”. (Search eBay for woodworking and other machine tools, and you’ll find many for sale from schools.) As Matthew Crawford points out in Shop Class as Soulcraft, the separation of thinking and doing is a misguided notion. Encyclopedic knowledge and critical thinking guide the hands of plumbers, carpenters, and motorcycle mechanics, to name only a few of the highly skilled and noble trades.

Bought with his own money, my son and I dragged his first car home with a chain and slowly worked together to rebuild it and make it road-worthy again. From the rebuilt carb to the new exhaust system, repacked wheel bearings with new ten-hole rims, and of course, a new head unit complete with amp and subwoofer, he was proud of that little Mustang and proud of his newly acquired skills. Much credit goes to my wife for pointing out that once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to pass some skills along, father to son.

Take a few moments and list the manual skills one of your parents or a favorite uncle had, and then circle the ones you don’t possess. Here’s a short list about my dad. He hated to pay someone else to do anything he even might be able to do himself.

- Welding (at work and at home)

- Butchering (as in the family meat-packing business)

- Carpentry (he built the house I grew up in, and several others)

- Woodworking (he made a lot of our furniture)

- Hunting (mostly bird, when he was younger)

- Gardening (usually started with a pick-up truck load of chicken manure)

- Car restoration and maintenance (he and my brother restored a 1966 Corvette)

- Mechanical work (he fixed appliances and built us go-carts and mini-bikes)

- Schnauzer grooming (the apple seldom falls far from the tree)

- Knitting (yup, and he taught my mother, too)

I could take a pretty good turn at most of these, although my welding and butchering would be pretty ugly, and I’m afraid I never found much call for knitting myself. (I personally don’t hunt for sport, but if it ever comes down to Bambi or my family going hungry, Bambi’s a goner.)

Craftsmanship is both the execution of a skill, and the desire to do something well for its own sake. Producing something physical, with hands guided by the mind, is extremely satisfying, particularly in a world where life is seemingly lived more and more passively . . . and more and more dependently.

What new manual skills would you like to learn? Even more important, what manual skills will you pass along?

You must be logged in to post a comment.